Vol. 40 (Number 2) Year 2019. Page 28

Vol. 40 (Number 2) Year 2019. Page 28

SOTO Vázquez, José 1; GÓMEZ-ULLATE, Martín 2; PÉREZ Parejo, Ramón 3

Received: 09/08/2018 • Approved: 01/12/2018 • Published 21/01/2019

ABSTRACT: At present, we can find some published research about Father Manjón and Ave María Schools and a wide acknowledgement of their innovative didactics. But very little is known of Ezequiel Fernández Santana (1874-1938), an extraordinary educational leader, model for social innovation and entrepreneurship who found an adult school, an agricultural labor union, wrote theatrical pieces, tales, novels and assumed the systematic use of photography as a means of observation and knowledge transfer in and out of school. |

RESUMEN: Actualmente, existen abundantes publicaciones sobre el Padre Manjón y las Escuelas del Ave María y cierto consenso sobre su papel didáctico innovador, pero poco se sabe y se ha publicado sobre Ezequiel Fernández Santana (1874-1938), un líder educativo extraordinario, modelo de innovación social y emprendimiento que fundó una escuela de adultos, un sindicato de trabajo agrícola, escribió obras teatrales, cuentos, novelas y asumió el uso sistemático de la fotografía como medio de observación y transferencia de conocimiento dentro y fuera del aula. |

The impact of photography and cinematography as teaching tools in the early decades of the twentieth century has been little studied in the European context. In USA, Cuban (1986) noted that "numerous studies in the 1920s and 1930s consistently proclaimed that films motivated students to learn". In Spain, however, there are few references in this emerging research line started by Del Pozo (2006), and followed by Comas (2010), Collelldemont (2010), Sanchidrián (2011) or Comas, Motilla and Sureda (2012).

In this context, the casual finding in a dumpster of over 200 glass photographic plates taken between 1915 and 1938 by Ezequiel Fernández Santana in the Parish Schools of Los Santos de Maimona and other subsidiary schools in Extremadura, represent an unprecedented event, given both the content of the images and the methodology behind them, which are unknown. It has not either been studied the aesthetic and didactic intention with which the author prepared and took his photographs, as he devoted a huge effort, not only economic to his school collection. We understand that Santana’s work is a milestone in school photography with didactic intentions worldwide. The photographic corpus has been catalogued and digitized thanks to a research project funded by the University of Extremadura (Soto, 2011a; Soto & Pantoja, 2011). It is still necessary to go further in its analysis and contextual interpretation, which reveals the universal and timeless vision of the work developed by this outstanding educational leader and pioneer, almost unknown today.

The school landscape in Spain that statistics show is very revealing (Núñez, 2005). 58% of the generation of 1907 had no education and more than 50% of students were out of school, while public institutions lacked commitment to improve this situation.

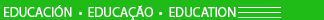

The Moyano Law 1857 (sections 100-105) was a major milestone in the evolution of the educational system in Spain in the nineteenth century, establishing the ratio of schools per capita that should exist in every location. However, the actual implementation of the law was very difficult due to the socio-economic circumstances (Cortes, 1998) and the lack of political willingness. We have collected information from more than 160 municipalities in Extremadura through different archival sources between 1857 and 1910 (Soto, Pérez & Pantoja, 2010; Pérez, Soto, Pantoja & Fraile, 2013) all indicating the type of school, teachers’ sex, salary and duration of stay in each school. We have also calculated the number of teachers per capita. These where the figures for the judicial district of Zafra, to which Los Santos de Maimona belongs:

Figure 1

Results of the distribution of population and appointment of teachers

in the Judicial District of Zafra between 1857 and 1910

Source: Soto, Pérez and Pantoja, 2010

We have researched the schools´ health conditions and educational facilities at the time (Soto & Samino, 2014) concluding that the number of actual schools was relevantly less than the number required by the Moyano Law. In the province of Badajoz, in 1908, there were 401 schools when it should have been nearly 300 more (Soto, Pérez & Pantoja, 2010). As for the high rate of illiteracy, Badajoz had a higher illiteracy rate of 85% in the late eighteenth century and remained around 84% in 1860 (España Fuentes, 2001), still being one of the three most illiterate Spanish provinces in 1930 (Vilanova & Moreno, 1992). More concretely, the figures for Los Santos de Maimona in 1910 registered 11 men and 10 women who could read, 1000 men and 930 women who could write out of 7304 inhabitants (INE, 1910). Differences in the two competences are due to the fact that for the enquiry purposes “to write” meant being able to sign and copy a text.

Fernández Santana (1919) explained the problem in a simple way:

“This serious and embarrassing situation, passed, however, unnoticed for everyone. For the rich, for they took their children to study primary education to private schools in nearby villages, and for the poor, because as they were illiterate, they did not understand the value of education, not did they care about their children’s lack of knowledge” (Original in Spanish, authors’ translation).

In this context, Ezequiel Fernández Santana decides to act in two main features that condition the entire education system: the high level of general illiteracy and the poor educational facilities. Both take him to create an original method of work incorporating photographs and films for education in and out of the classroom.

Ezequiel Fernández Santana promoted several educational and social institutions in his first assignments as a priest in Bodonal de la Sierra and Fregenal de la Sierra (1905-1909), and after in Los Santos de Maimona (1909-1938).

Based upon equalitarian principles, the school should be “for all, the rich and the poor, not being free for everyone, but only for the poor, but all must be together, without distinctions, preferences, and preserving the privacy and secret of who paid and who did not” (Fernández Santana, 1922).

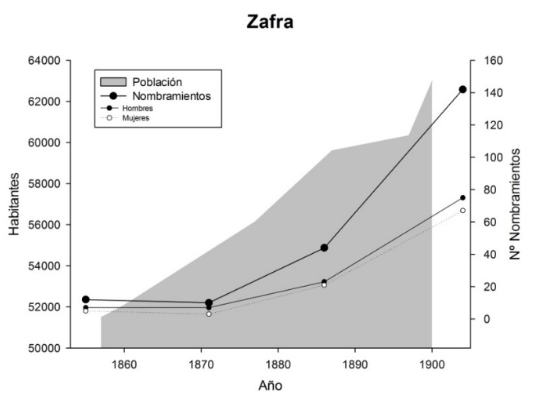

Figure 2

Agriculture class. A section of the Alumni Board, published in the book Organización

y Procedimientos (Fernández Santana, 1920). Free Adult School for 14 to 18 year old

teenagers, with courses held in the evening to assure that these could attend them

after work. Maimona Foundation File (Box 1).

In the latter, he found in 1909 the Parish Primary School while he engaged in teaching primary education to laborers and farmers in a night school for pupils over 14 years old (see fig. 2). Two years later he found the Secondary School and a Teachers Training Seminar to expand his particular pedagogy and his “Work’s organization” (Fernández Santana, LEP, 1917). In this line, he writes “Pedagogía Deportiva” (Sporty Pedagogy) preluded by these words from Polo Benito (Fernández Santana, 1922):

“And here I find, readers, one of the main merits of this book, which is called Sporty Pedagogy, first practiced with the disciples, then, given the results, written for teaching parents and teachers. Pedagogy is the set of personal experiences, practically contrasted procedures, which equally and harmoniously embracing body and soul, take care about spirit and matter in the same degree, to make teaching an entertainment, a playground, a sport”.

Figure 3

The Children’s Battalion pledge loyalty to the flag in the courtyard of the Parish School.

Photo published in the book “Nuestra Escuela” (1919), under the title

“El Patrono de la Escuela”. Maimona Foundation File (Box 4).

Within a lifelong learning and social action perspective Fernández Santana found an Alumni Board of free and voluntary assistance for adults having passed Primary Education. He managed to have permissions to run the military instruction in this organization avoiding the young men’s leak the military service supposed for every Spanish village, which was a relief for households economy (see fig. 3). Father Manjón (1921) wrote about this: “Now that all nations are but hidden military camps, since all the useful men are soldiers on active or reserve, D. Ezequiel, educator and pacifist, has organized his people in a regiment, uniform and all, well-educated and disciplined”.

Santana also promoted a Community Savings Fund [...] to be distributed among the partners in times of need, a fund for old-age retirement and disability for work but very conscious that [...] it had for mission to spread the habit of saving, thus prohibiting loans and repayments [...] (Fernández Santana, 1917).

Through this system and organizations founded by Santana, children began primary school at six, at fourteen in adult school and at eighteen, if they wished, joined the Board of alumni, where they were admitted as aspirant partners in the Union of alumni (Fernández Santana, LEP, 1918), which shows a clear commitment to contemporary lifelong learning principles. Throughout all this period, he tried to motivate students with awards and grants.

The success and impact of the adult school was evident from the increasing numbers of inscriptions (125 in 1909, 265 in 1912) and is presented by its founder in a conference:

“There are someones that during the six months that classes last do not miss a single night. Many who do not reach five fouls, and not a few, who have to walk and retrace several kilometers to attend classes and return to the villages, and this even in raw winter nights” (Fernández Santana, 1912, p.13) After completing this educational network, his main concern was to export the model to other locations, as the Ave Maria Schools of Granada were doing at the time (Manjón, 1921; Montero, 1999). And for this purpose he uses photography as well (see fig. 4).

Figure 4

Reading class with the youngest pupils, learning the alphabet.

Published in the book “Pedagogía Deportiva” (1922). Family File (Box 2).

As well as more than 20 schools, throughout his life, Fernández Santana found agricultural unions, savings banks, brass bands, military leagues, adult schools, and wrote pedagogical treaties, journal articles, novels and theatrical pieces (Soto, 2011b; Sánchez, 1994).

He struggled throughout his short life to set up self-sufficient, autonomous schools and persons, a revolutionary movement from inside the system that did not passed unnoticed: “There are rich people who say to me, <<but, Father, what are you doing with that! But don’t you see that with what you’re doing it is going to be impossible to master these people?>> Ah! But do you think, I say, we are still in the time of Aristotle in which they believed that some men are born to be free and others to be slaves? You are wrong” (Fernández Santana, 1920).

This research study aims to highlight and bring to academic discussion at the international frontline the important role of Ezequiel Santana, an educational leader and innovative teacher almost unknown and underestimated in the History of Education. Our research explores to what extent his pedagogical principles and teaching strategies –sharing those of Ave Maria Schools- were innovative for Spain, Europe, and the world, one hundred years ago. This photographical set represents an unpublished and unique material which shows that Ezequiel Santana was one of the pioneer teachers in Europe to use photography and cinema as educational tools. It is valuable due to the amount of photographs (220 images), its thematic consistency and its pedagogical perspective.

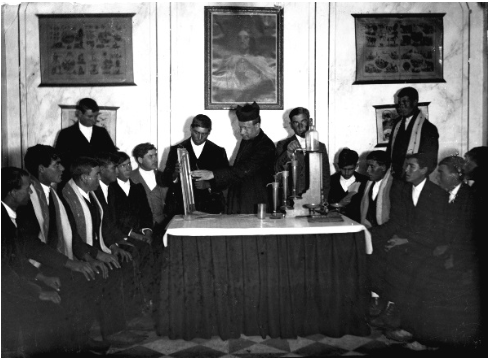

The original glass plates of Ezequiel Fernández Santana´s photographs, taken between 1915 and 1938, were found in a dump. Our Research Group has later restored and digitized them according to the contemporary criteria for documentary collections, as well as catalogued for their correct identification and classification (see fig. 5).

Figure 5

Original glass plates of Ezequiel Fernández Santana photographs, taken between 1915 and 1938.

Source: Authors from the Maimona Foundation Archives.

Santana’s pictures constitute a milestone in the history of school photography. From an interdisciplinary approach, this paper describes and analyzes the life, achievements and historical context of Ezequiel and some of his valuable photographic material from the point of view of content, narrative discourse and educational vision, reflecting the use of photography to transmit a series of educational content through innovative teaching techniques.

The Spanish ecclesiastical hierarchy was contrary to the cinema as a teaching tool. The control of the Catholic Church and its censorship of cinematographic projections largely prevented the use of this element in the Spanish parishes. Continuous measures of censorship were supported by the enactment of laws as the Royal State Act of 1913, and acclaimed by Catholic newspapers as "El Debate" (Pelaz, 2005).

Fernández Santana and Polo Benito’s friendship was fundamental for purchasing and using a cinematograph convinced by his very attractive arguments about the technical and methodological possibilities of film. The dean of Plasencia, Polo Benito, pointed on the incorporation of cinema in teaching to follow schools that were at the forefront of educational advancement:

“What do you think is the shortest way between the object and its knowledge? What are the means for achieving a more effective education? The method adopted in your schools gives us the answer: To see the object, to have it in front of your eyes [...] We see the object on the canvas in which it is projected and at that moment, our eyes wounded with its image, the imagination gets impressed: the seen object, almost lived, boost intellectual work, ideas come around it [...]”.(Fernández Santana, 1915).

In 1915, these will motivate our innovative educational entrepreneur to acquire for the schools a machine from Enermam Kinok. We find constant references of the use of films in Fernández Santana’s schools as well as in academic events (Fernández Santana, 1915). Also about its use as an entertainment complement to school activities and as a powerful information medium:

“Every month there will be a literary evening in the auditorium of the school. This month it will take place on the 14th and will consist of several speeches and poems by students, a dramatic representation and the projection of several films, including one of the current war, filmed in Russian-Turkish Caucasus forefront, so interesting and detailed that gives you the impression of being in the war”.

One century after Fernández Santana first photographs were used in the classroom, the collection developed by him between 1915 and 1938 is an excellent material on school picture, so far almost unstudied and unpublished, needing thorough analysis in the line established by Warmington et al. (2011) to preserve and study photographic material before it could disappear.

His legacy is composed of a set of plates divided into two different funds. There is a set of 138 negatives in possession of Maimona Foundation coming from the discovery of 10 boxes in a dumpster near the priest’s house, six of them without any registration, but some words written on the covers of some of them: Union; Building; Drawings and exhibitions; Sports; Night school; Primary School; Secondary school; Building and village landscape. Completing the collection, Fernández Santana’s relatives keep three boxes with over 82 plates that have also been restored by the same procedure. We have classified the fund by subjects in the following table:

Table 1

Subjects, number of images and location of photographic funds

Content |

Nº photographs |

Location |

Agriculture |

17 |

Family File and Maimona Foundation File |

Reading |

11 |

|

Gimnastics |

11 |

|

Christian doctrine |

9 |

|

Arithmetic |

7 |

|

Geography |

5 |

|

Geometry |

4 |

|

Biology |

2 |

|

History |

2 |

|

Family portraits |

26 |

Family File, Maimona Foundation File and missing File |

The school building |

22 |

Family File and Maimona Foundation File |

Teaching staff |

16 |

Family File, Maimona Foundation File and missing File |

The Escorial |

11 |

Family File |

Schools postcards |

11 |

Family File |

Military league |

11 |

Family File and Maimona Foundation File |

Bullfighting lessons |

10 |

Family File |

Adult school and unions |

10 |

Family File and Maimona Foundation File |

Students groups |

9 |

Family File, Maimona Foundation File and missing File |

Musical groups |

8 |

Family File, Maimona Foundation File and missing File |

Savings bank |

6 |

Family File and Maimona Foundation File |

Dining-room and desks |

6 |

Family File and Maimona Foundation File |

Student’s works |

5 |

Maimona Foundation File |

Subsidiaries schools |

5 |

Missing File |

Theatre performances |

5 |

Family File and Maimona Foundation File |

Los Santos de Maimona |

3 |

Maimona Foundation File |

Gratitude tribute |

2 |

Maimona Foundation File |

The bulk of his work are photographs that treat the image as a teaching resource for teacher training (see fig. 6) finding in recreation with images the ideal vehicle for the transmission of his school model and educational and social work. With the display of school materials, reflecting the place and role of teachers or the classroom organization, he aimed to transfer methodological aspects throughout subsidiary schools. He also used his photographs as a propaganda to raise funds for the ailing economy of his social work, which required large and own private donations to bear the high expenses of building maintenance, salaries of teachers, etc.

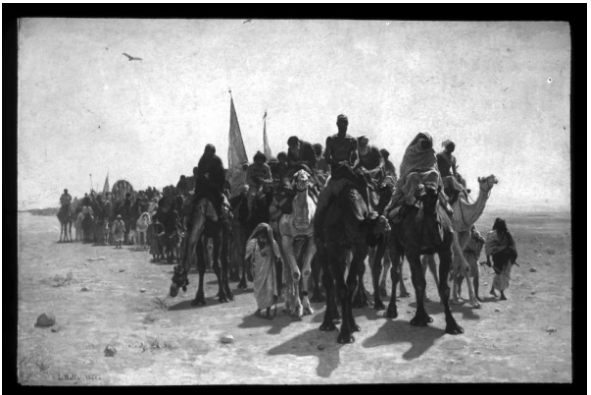

Figure 6

Photograph Leon Belly’s picture: Pilgrims going to Meca, 1861 (PROJECTIONS – MAZO-PARIS

/ Autorisation de Projeter). "L'Ecole sans / Pelerins à la / Mecque". Nº 12. Family File (Box 2).

It is important to highlight the artistic intentionality in the composition. There is a previous study of the outlet, lighting and the particular school moment to be recorded in the still image (fig. 7). So, we cannot talk about a spontaneous and casual work, but a measured artistic and studied effort.

These images were created as illustrations to accompany his educational foundations, they complemented texts, giving a cosmopolitan and modern look in a context away from the immediate reality of the rural environment in which they arise.

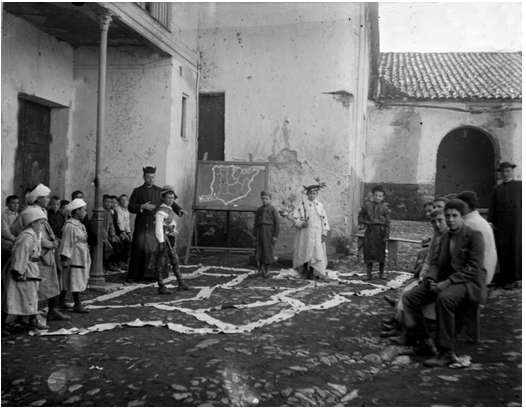

Figure 7

Spanish History class. Photo first published as an illustration in the magazine

“La Escuela Parroquial” (1917), afterwards also in “Pedagogía Deportiva”.

The students act out all the significant events of Spanish History related by the teacher.

They play their performance on a map of the Peninsula which they have made themselves

indicating the outlines with coloured ribbons. Maimona Foundation File (Box 1).

Even if in the nineteenth century the use of panoramic photographs for teaching and scientific purposes is anecdotal (Warner, 2002), the use of the photographic image as an educational resource has had ups and downs throughout the 20th century. Appearing occasionally since 1900, it would not be a frequent occurrence until 1930 (Cuban, 1986). One of the milestones that marked the beginning is the appearance of the Catalogue of Educational Motion Pictures, which released in 1910 George Kleine. Oliver Gaycken (2004) nevertheless argues that while it was aligned with modern pedagogical research promoting visual means as the most efficient form of instruction, the catalogue, on the other hand, recalled the collections of natural artifacts that were called “cabinets of curiosities” in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The use of photographs in the classroom will not be adopted as a normal practice until the 1920s, both to bring World War I to class (Cuban, 1986) and for agricultural education, later in the thirties (Warner, 2002). But visionaries and pioneers as Edison argued, in 1913, that traditional textbooks would be replaced by visual means and people unfamiliar with these means would be the illiterates in the future (Flusser, 2012). These have been seen as an example of overselling technology as the claims that television would be a revolutionary pedagogical tool (Cole, 2000), but if we think about Internet and the ICT revolution, Edison’s statements are close enough to current trends.

The use of photography for educational purposes must be understood as a modern concept (Williamson, 1994). The main causes of its late inclusion were equipment’s high costs, ill-equipped centers and little or none trained teachers in the use of these media and their narrative language (Cuban, 1986). The same happened to documentary films that will appear in the 30s (Warminton, Van Gorp, & Grosvenor, 2011).

Ezequiel Fernández Santana’s first plates, dating from 1915, makes him one of the pioneers in the educational use of photography in Spain, Europe and worldwide. But his work and breakthroughs have been little appreciated because he was viewed as persona non grata by the two warring factions during the Spanish Civil War.

His own words reveal how close he was to other of the education leaders and pioneers of his time, Rudolf Steiner, with whom, without receiving any news or influence, he shared the core principles for education:

“[…] instead of being imaginative, let's make [education] intuitive, rather than memoristic, let's make it reflexive; rather than theoretical, let's make it practical; enjoyable rather than mortifying; active instead of being passive”. (Fernández Santana, 1920:15)

And as if he was foreseeing the Waldorf schools:

“We should make school enjoyable; children are outdoors in the sun; introduce things that please them; make the school as a second home, as the country itself with all the appeal that has for children; make the school active, ensuring that the student take part in everything and that he himself is part of the teaching, besides being disciple [...] This is our way, leading to each subject these pedagogical principles”.

It is amazing for cultural comparisons how these two visionaries, Steiner and Fernández Santana, coming from such different socio-cultural contexts and backgrounds could share so many principles, practices and ideas on how education should be and how it could change society. They were both models that integrated social action and self-sufficiency for persons and organizations, no matter if they were deeply insufflated by completely different ideologies.

Spain, nowadays, the EU country presenting the worst results in international educational assessment (PISA, PIRLS), is far from this school model. Our educational leaders could find an excellent source of inspiration in the life and work of Ezequiel Fernández Santana, a “Spanish Rudolf Steiner”, almost unknown and unstudied.

COLLELLDEMONT, E. (2010). La memoria visual de la escuela. Educatio Siglo XXI, 28 (2), 133-156.

COMAS RUBÍ, F. (2010). Fotografia i història de l’educació. Educació i Història: Revista d’Història de l’Educació, 15, 11-17.

COMAS, F., MOTILLA, X. & SUREDA, B. (2012). Fotografia i historia de l’educació. Iconografía de la modernització educativa. Palma de Mallorca: Lleonard Muntaner.

CUBAN, L. (1986). Teachers and machines: The classroom use of technology since 1920. New York: Teachers College Press.

DEL POZO, M. M. (2006). Imágenes e historia de la educación: construcción, reconstrucción y representación de las prácticas escolares en el aula. Historia de la Educación, 25, 291-315.

ESPAÑA FUENTES, R. (2001). La educación en Extremadura en el s. XIX: reformas introducidas durante el sexenio democrático (1868-1874). Revista de Estudios extremeños, T. LVII (1), 131-179.

FERNÁNDEZ SANTANA, E. (1915). Las escuelas parroquiales. “Boletín Parroquial”. Tip. de Sánchez Hermanos.

FERNÁNDEZ SANTANA, E. (1917). Las cajas rurales extremeñas: Tip. de Sánchez Hermanos.

FERNÁNDEZ SANTANA, E. (1919). Nuestra Escuela. Los Santos de Maimona: Tip. de Sánchez Hermanos.

FERNÁNDEZ SANTANA, E. (1920). Organización y procedimientos pedagógicos en las Escuelas Parroquiales de Los Santos. Madrid: Ed. Reus.

FERNÁNDEZ SANTANA, E. (1922). Pedagogía Deportiva. Badajoz: Joaquín Sánchez.

FLUSSER, V. (2012). Towards a Philosophy of Photography. Reaktion Books.

INE (1910). Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Censo de analfabetos. Badajoz.

KLEINE, G. (1910) Catalogue of educational motion picture films. Ed. Chicago.

MANJÓN, A. (1921). Hojas Cronológicas del Ave-María. Granada: Imp. Escuelas del Ave-María.

MONTERO VIVES, J. (1999). Las visitas a las Escuelas del Ave María, en tiempos de D. Andrés Manjón. Granada: Imp. Escuelas del Ave-María.

PELAZ LÓPEZ, J. V. (2005). Los católicos españoles y el cine: de los orígenes al nacionalcatolicismo. In J. L. Ruiz Sánchez (Ed.), Catolicismo y comunicación en la historia contemporánea (pp. 76-81). Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla.

PÉREZ PAREJO, R., SOTO VÁZQUEZ, J., PANTOJA CHAVES, A. & FRAILE PRIETO, T. (2013). Catálogo para el estudio de la educación primaria en la provincia de Cáceres en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. Cáceres: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Extremadura.

SÁNCHEZ PASCUA, F. (1994). La Obra Socio-Educativa de Ezequiel Fernández Santana. Badajoz: Universitas Editorial.

SANCHIDRIÁN BLANCO, C. (2011). El uso de imágenes en la investigación histórico-educativa. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 29 (2), 295-309.

SOTO VÁZQUEZ, J. (2011a). La fotografía escolar de Ezequiel Fernández Santana (1915-1938). Los Santos de Maimona: Fundación Maimona.

SOTO VÁZQUEZ, J. (2011b). Pedagogía Deportiva. Madrid: Cultiva Comunicación.

SOTO VÁZQUEZ, J. & SAMINO LEÓN, A. (2014). La enseñanza pública en Los Santos de Maimona a través de sus documentos. Colección Pedagogía, nº 16. Badajoz: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Diputación Provincial de Badajoz.

SOTO VÁZQUEZ, J. & PANTOJA CHAVES, A. (2011). Catálogo de la exposición “La fotografía escolar de Ezequiel Fernández Santana (1915-1938)”. Colección Educa-Imagen, nº 1. Los Santos de Maimona: Fundación Maimona.

SOTO VÁZQUEZ, J., PÉREZ PAREJO, R. & PANTOJA CHAVES, A. (2010). Catálogo para el estudio de la educación primaria en la provincia de Badajoz durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX (1857-1900). Colección Pedagogía, nº 14. Badajoz: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Diputación Provincial de Badajoz.

VILANOVA RIBAS, M. & MORENO JULIÀ, X. (1992). Atlas de la evolución del analfabetismo en España de 1887 a 1981. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

WARMINTON, P., VAN GORP, A. & GROSVENOR, I. (2011). Education in motion: uses of documentary film in educational research. Paedagogica Historica, 47 (4), 457-472.

WARNER MARRIEN, M. (2002). Photography: a Cultural History. 2nd Edition. London: Laurence Kings Publishing.

WILLIAMSON, J. (1994). Family, Education, Photography. In: N. B. Dirks, G. Eleye & S. B. Ortner (Eds.), Culture / Power / History: A Reader in Contemporary Social Theory (pp. 236-244). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

1. Department of Literature for Children & Youth in the Didactics of Social Sciences. University of Extremadura, Teacher Training College. Associated Professor. jsoto@unex.es

2. Department of Didactics of Arts, Music and Body Expression. University of Extremadura, Teacher Training College. Researcher. mgu@unex.es

3. Department of Literature for Children & Youth in the Didactics of Social Sciences. University of Extremadura, Teacher Training College. Associated Professor. rpp@unex.es