HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN

HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN Espacios. Vol. 37 (Nº 22) Año 2016. Pág. 16

Eliana Andréa SEVERO 1; Julio Cesar Ferro de GUIMARÃES 2; Claudio ROTTA 3

Recibido: 01/04/16 • Aprobado: 02/05/2016

4 Discussion of proposed model

ABSTRACT: The environmental problems in modern society and the business world have become more relevant through factors related to increasing industrialization and the scarcity of natural resources. This study aims to analyze the correlation between the constructs of environmental management, social responsibility and organizational performance in the 239 companies that are a part of the Metal-Mechanic Automotive industry Brazilian. To do this, the data analysis technique of Structural Equation Modeling was used. The companies that implement environmental programs and actions have superior organizational performance, when compared to companies with few or do not develop actions in the social and environmental sphere. |

RESUMO: Os problemas ambientais na sociedade moderna e o mundo dos negócios tornaram-se mais relevante por fatores relacionados à crescente industrialização e a escassez de recursos naturais. Este estudo tem como objetivo analisar a correlação entre os construtos de gestão ambiental, responsabilidade social e desempenho organizacional nas 239 empresas que fazem parte da indústria metalmecânica automotiva brasileira. Para isso, foi utilizada a técnica de análise de dados de modelagem de equações estruturais. As empresas que implementam programas e ações socioambientais apresentam uma performance organizacional superior, quando comparadas as empresas que apresentam poucas ou não desenvolvem ações na esfera social e ambiental. |

Awareness of environmental problems in modern society and the business world have become more relevant through factors related to increasing industrialization, the scarcity of natural resources, the population explosion and excessive urbanization. This awareness has been caused by changes in consumer behavior, as they begin to demand that companies' take a stance on environmental and social issues. Environmental problems lead people to expand their horizons over time. While neoclassical economics analyze the short-term effects, the ecology time scale expands to the long term.

In the last few decades, there have been changes in the way organizations see the environmental issues related to their production processes. Companies have modified their way of doing business to at least reduce adverse environmental impacts (York et al., 2003; Guimarães et al., 2014; Severo et al., 2015). The perception that had existed among businesspeople up until the last few decades, that adopting efficient social and environmental management practices negatively impacts organizational performance, has gradually become outdated.

With increasing environmental degradation, environmental management and social responsibility have become seen as practices that strive for sustainability, contributing to organizational performance (Halkos; Evangelinos, 2002; Gunawan, 2007; Mattila, 2009; Molina-Azorín et al., 2009; Hofmann et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2012; Ngai et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the adoption of environmental practices and social activities depends a great deal, on how the top management perceives and addresses these issues; if they are seen as opportunities or threats (Sharma, 2000; Darnall et al., 2008). The adoption of environmental practices and social initiatives is a decision that must involve the entire company, as it commits itself to applying its principles and values, minimizing risks in each stage of implementation for socio environmental projects. An appropriate strategy is one that neutralizes threats and takes advantage of opportunities, while it also capitalizes on strengths and prevents or repairs weaknesses (Barney, 2013).

The Automotive Metal-Mechanic Cluster (AMMC) of Serra Gaúcha is the second largest AMMC in Brazil, as it concentrates a large number of companies in the auto parts, agricultural machinery and transportation vehicles industries. A large part of the 2,588 companies in the AMMC are micro and small enterprises (95%), generating close to 62,775 jobs (Simecs, 2013). The AMMC includes 17 municipalities in the Serra Gaúcha region, where Caxias do Sul is home to the largest number of companies. In the Caxias do Sul region, the automotive chain produces trucks, buses, agricultural machinery, auto parts and road equipment. In 2010, the city of Caxias had a population of 435,564 inhabitants and 31,016 companies in the various sectors listed above (Ibge, 2013). Based on this data, there is an estimated rate of 14 inhabitants per company in Caxias do Sul, placing it near the highest global entrepreneurship rates in the world.

Still, it is important to note that the metal-mechanics sector is part of the Metallurgical Industry category, which has an "A" classification for potentially polluting activities and a High rating for natural resource use (Brasil, 2000). In this context, the metal-mechanics sector is characterized as "A High", which means it has a high environmental impact because it consumes a high volume of natural resources and creates a series of pollutants. In this sense, environmental management and social responsibility are extremely important to the availability of natural resources, lower environmental impacts and organizational performance, so that companies can remain competitive. However Severo and Guimarães (2015) warn that environmental sustainability is not yet perceived as a strategic area AMMC the metal-mechanic companies operating in southern Brazil.

Based on the aforementioned information, this study aims to analyze the correlation between the constructs of environmental management, social responsibility and organizational performance at 239 companies in the AMMC of Serra Gaúcha. The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique was used to analyze data for this purpose. In addition to this introduction, the article is structured into four other sections: the theoretical framework that lists the research hypotheses, the methodological processes and research techniques used in the study, the presentation and discussion of the results, and the conclusions drawn.

Various points in the research show that organizations have increasingly included environmental practices and social responsibility initiatives for their employees and the communities they are in. Organizations' adherence to sustainable development initially comes from the outside in, as a way to counteract criticisms and objections made by numerous government agencies and civil society organizations that aim to make companies responsible for the social degradation and environmental processes that affect the planet. In this environment degradation process there are risks on water quality (Wu et al., 2014), the issue of solid waste (Li et al., 2009; Agboola, 2014), wastewater, air pollution and the use of contaminants in products, this sense there is need for policies government environmental conservation and corporate sustainability actions (Zhou et al., 2011; Morrison et al., 2012; Stough-Hunter et al., 2014).

Social and environmental responsibility are solidified by the inclusion of the environmental and social effects that they produce during the decision making process, showing that an organization's commitment is not solely based on meeting economic or legal requirements. Consequently, companies have already perceived that respecting human beings and the environment are among the main factors that directly affect organizational success, as a way to embrace competitive advantage in the marketplace (Grayson; Hodges, 2004; Porter; Kramer, 2002; Seiffert, 2008; David et al., 2013; Kluga; Kmoch, 2015).

In Brazil, organizations count on the support of the Instituto Ethos de Empresas e Responsibility Social, created in 1998, which is an exemplary entity that guides companies in terms of social and environmental initiatives. The mission of Instituto Ethos is to create awareness, mobilize and help companies manage their business in a socially responsible manner, making them partners in the construction of a just and sustainable society, preserving environmental and cultural resources for future generations, respecting diversity and reducing social inequality (Instituto Ethos, 2013). In this context, Instituto Ethos provides a series of indicators through a questionnaire that can be used as an instrument for self-evaluation and learning. Companies can diagnose their situations and raise subsidies for strategic planning in seven areas, which include: i) the environment, ii) the community and iii) society. Companies that are interested in evaluating their social and environmental responsibility initiatives can answer the Ethos Indicators and verify their strong points and opportunities for improvement (Instituto Ethos, 2013).

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a network-based organization that is a global pioneer in sustainability reports. Organizations can use GRI indicators to measure, report and disseminate information to internal and external stakeholders on the economic, environmental and social impacts (Gri, 2013).

In terms of the variety of research on sustainability, Grayson and Hodges (2004) show that when people are forming their opinions of a company, they pay more attention and place more consideration on the company's contribution to social causes and their relationship with the environment than the brand's reputation or financial standing. However Nikolaou et al. (2013) observed that the literature indicates that asymmetric information generates various problems for the actors of financial markets such as incomplete information for investment decisions and lending procedures, misallocation of financial market funds, the underestimating of stock price securities, and poor environmental risk management choices. This indicates the need for more adequate financial metrics evaluation for environmental sustainability.

According to González-Benito and González-Benito (2006), size (measured by the number of active employees), is one of the structural variables that most influences environmental initiatives at companies, because large companies have more resources available to invest in environmental management. They also receive more pressure from social and economic environments and are frequently primary targets for local governments and environmental non-governmental organizations.

In this scenario, Elkington (1999) presents the triple bottom line model, based on management for obtaining positive economic, social and environmental results, called pillars of sustainability. These pillars are not exclusionary, which shows the correlation of environmental practices and social initiatives at organizations.

The benefits of developing sustainable business activities that include environmental and social projects emerge as a competitive advantage and a vehicle for resources that are more efficient, thereby reducing waste and opening up new markets (Darnall et al., 2008; Potts, 2010). Therefore, it is clear that there is a positive correlation between environmental management and social responsibility, which is shown in H1.

H1: Environmental management and social responsibility are positively correlated.

Environmental management combined with a planning strategy is able to balance the phenomenon of direct and indirect interference (human, economic, social) in order to create compatible development in the medium and long term (Mörtberga et al., 2007). The benefits of developing sustainable business activities emerge as a competitive advantage for resources that are more efficient, reducing waste and opening up new markets (Ngai, 2013; Potts, 2010, Mörtberga et al., 2007).

Organizational performance can be understood as the quality of goods and services, profitability of new products, returns on investments and assets and reductions in operational costs, making up companies' global performance compared to their competitors (Aragón-Correa et al., 2008).

The environmental strategy for appropriate use of resources is revealed as a fundamental attribute for economic competitiveness (Potts, 2010; Claver et al., 2007), creating opportunities for innovation and gaining customer loyalty, contributing to competitive advantage over competitors (Kassinis; Soteriou, 2003) and most importantly, improving the corporate image (Mattila, 2009).

An organization's adoption of environmental practices is motivated by external and internal reasons. The internal reasons include reducing costs, updating technology, optimizing production processes and developing an environmentally friendly internal culture (Henry; Kato, 2011). The external reasons include preventing environmental accidents caused by society and the demands of interested parties, such as the globalized market, financing agencies, the local community, civil society organizations and governments (Seiffert, 2008; Welch et al., 2002).

Environmental responsibility is companies' natural response to their new client: the environmentally responsible consumer. Jabbour et al. (2012) performed a study of 75 companies in the Brazilian automotive industry, and found that environmental management positively influences companies' operational performance. The study done by Lin et al. (2012) of 208 companies in Vietnam shows that environmental management is positively linked with organizational performance. Halkos and Evangelinos (2002) highlight the fact that implementation of environmentally friendly practices is positively correlated with reductions in production costs and improving company image, which contributes to organizational performance. In this scenario, Kassinis and Soteriou (2003) show a strong connection between environmental practices and organizational performance, with an emphasis on the client's satisfaction and loyalty.

To this end, the use of environmental management is related to decreased consumption of inputs and raw materials, reduced production costs, increased productivity and competitive edge and an improvement in organizational performance (Halkos; Vangelinos, 2002; Lin, 2012; Kassinis; Soteriou, 2003; Buysse; Verbeke, 2003; Handfield et al., 2003; Severo, 2013; Guimarães et al., 2014).

Overall, an emerging consensus in the research shows that there are positive organizational performance results correlated with the adoption of environmental management practices, especially in organizations that are environmentally proactive (Molina-Azorín et al., 2009; Claver et al., 2007; Gonzalez-Benito; Gonzalez-Benito, 2005; Aragón-Correa, 1998; Iraldo et al., 2009; Crowe; Brennan, 2007; Yang et al., 2010; Guimarães et al.; 2015).

In this context, it is assumed that there is a positive correlation between environmental management and organizational performance, as highlighted in H2.

H2: Environmental management is positively correlated with organizational performance.

Various empirical research techniques have been used to analyze the correlations between social responsibility and organizational performance. In this scenario, a variety of social responsibility measures, changes in organizational performance and results have emerged. The growing public concern and social demands towards the future society also are putting pressure on policy makers (Ittipanuvat et al., 2014).

Griffin and Mahon (Griffin; Mahon, 1997) performed a study that analyzed 51 research projects conducted since the 1970s, and they highlighted a number of studies that explored the relationships between corporate social responsibility and organizational performance. However, no strong consensus exists, because the results have often been contradictory, even within the same analysis. To the authors, this lack of consensus is the result of the diversity of social and organizational performance measures being used, as well as the diversity of the sectors involved in each study.

Graves and Waddock (1994) note that there is a positive relationship between social performance and institutional property. In this sense, a company that invests in social responsibility does not become less attractive to institutional investors. In terms of social concerns and economic interests, these investors select organizations that are known to have a socially responsible attitude. Ruf et al. (2001) highlight that investors may not only be concerned with an organization's economic-financial performance (which contradicts neoclassical theory), but with their social responsibility initiatives as well.

Mahoney and Roberts (2012) verified the relationship between social and environmental achievements and financial performance at Canadian companies. According to the authors, there is a significant and positive relationship between social and environmental achievements and financial performance at companies. Simpson and Kohers (2002) performed a study at 385 American financial institutions from 1993 to 1994. The authors believe there is a positive correlation between corporate social responsibility indicators and the financial indicators at these companies.

Preston and O'Bannon (1997) analyzed the correlation between social performance and financial indicators at 67 American companies from 1982 to 1992. According to the authors, financial performance influences social performance and vice-versa, with a synergistic relationship between the two.

In the scenario, Roman et al. (1999) analyzed 52 studies on social responsibility and financial performance published over the course of 25 years. The results showed that 22 studies found a positive correlation between social and financial performance, 14 found no effects or were inconclusive, and 5 studies presented a negative relationship. The authors believe that if the relationship between financial and social performance can be positive in general, it can be consistent with the results of the most recent research. Given this information, a large part of the studies reviewed showed a positive correlation between social responsibility and organizational performance (Guimarães et al., 2015). Therefore, we propose H3.

H3: Social responsibility is positively correlated with organizational performance.

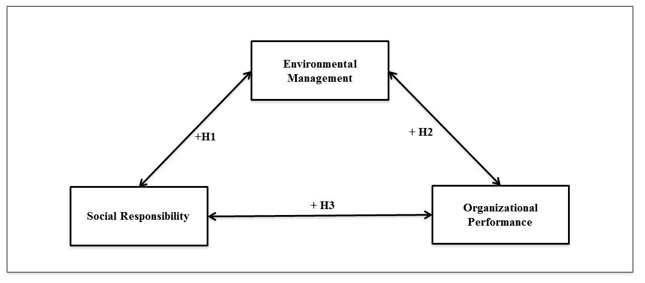

Based on this, Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework including the three hypotheses presented in the study.

Figure 1 – Model proposed hypotheses

Source: Authors (2016).

To investigate the relationships between the constructs proposed in this study, a descriptive survey using questionnaires was applied. The questionnaire was created based on a review of the literature on environmental management, social responsibility and organizational performance. In order to ensure that the questionnaire was easy to understand, a pre-test was conducted at 27 AMMC organizations in the Serra Gaúcha region. The questions used in the survey are presented in Table 1. For the development of the questionnaire was used as a basis: i) Social Responsibility – adapted from Ethos Institute (2013) and Gri (2013); ii) Environmental Management – adapted from Ethos Institute (2013), Gri (2013) and Severo (2013); iii) Organizational Performance – adapted from Paladino (2007).

The data collection took place from January to June of 2013. Initially, 912 companies were chosen to receive the questionnaire (from the 2,588 companies in the Serra Gaúcha region AMMC), which is a non-probabilistic sample, for convenience purposes. The company contacts were obtained through the 2011 Rio Grande do Sul Industrial Registration, provided by the Federation of Industries of the state of Rio Grande do Sul (Fiergs, 2011). The questionnaires were sent via e-mail, and 30 days later only 82 had responded. Subsequent phone interviews were conducted, which obtained 164 more responses, for a total of 246 cases. 7 questionnaires were eliminated due to the lack of answers to all of the questions, which led to a valid sample of 239 cases.

For the data collection, it was requested that companies participating in the research respond to the questionnaire presented in Table 1 according to a level of agreement or disagreement. The scale used was modeled after the Likert 5-point scale, with the extremes being (1) I completely disagree and (5) I completely agree (Byrne, 2009). The survey respondents were managers (directors, managers and coordinators) who are responsible for the Production and Socio environmental Management departments at their companies.

Índice |

Integrated model final |

Chi-square |

445.890 |

Degree of freedom (DF) |

167 |

Chi-square divided by the Degree of freedom |

2.67 |

Level of probability |

0,000* |

KMO - Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy |

0.906 |

CFI - Comparative Fit Index |

0.904 |

NFI – Normed Fit índex |

0.855 |

GFI – Goodness of Fit Index |

0.844 |

AGFI - Adjusted Goodness of Fit |

0.804 |

RMSEA - Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation |

0.080 |

Confiabilidade Composta |

0.977 |

Composed confiability |

0.686 |

Cronbach's Alpha |

0.926 |

Table 1 – Observable and Latent Variables – Varimax Rotation

Source: Authors (2016).

SEM was used to analyze and interpret data, because it uses a set of statistical analysis methodology procedures that allow for simultaneous examination of a series of dependence relationships (Hair Jr. et al., 2009; Kline, 2010). The statistical treatment and data analysis was performed using Version 20 of SPPS® software for Windows® and Version 18 of the AMOS™ software coupled with SPPS® was used to systematize the SEM methodology, because according to Byrne (2009), AMOS™ presents the functions necessary for the analysis and modeling that SEM requires.

Before individually validating the latent variables (constructs), which was done through Confirmatory Factor Analysis, an analysis was done of the assumptions of normality in the observed variables.

In the analysis of the assumptions of normality in the observed variables, indicators of kurtosis, skewness, sample means and multivariate distribution were calculated and examined. The Mardia Coefficient was used to analyze the kurtosis of each observable variable (Mardia, 1971; Bentler, 1990). This study identified amounts lower than 5, which shows they are significant and that the data has a normal distribution. The observed variables show values near zero for Pearson's Coefficient of Skewness, which according to Marôco (2010) shows moderate skewness.

The data was purified through an evaluation of missing values and outliers (univariate and multivariate). In the data collected, there was 2.85% non-response rate for a particular variable, which Kline (2010) considers to be a low missing level. He recommends a rate below 5%. There were no outliers found through the combination of univariate and multivariate analyses, which included calculating the Z scores to evaluate if there were cases with amounts higher than |3| for each variable. According to Hair Jr. et al. (2009), these should be excluded from the final sample. The Mahalanobis distance was used to identify multivariate outliers in cases with more extreme scores. However, this test did not identify any issues, since it did not show a significant distance between the individual amount and the sample means obtained (Kline, 2010).

It is important to note that in the final sample of 239 cases, 76% are micro and small companies and 14% are medium and large companies. For this reason, an ANOVA was performed on the company sizes, to verify whether there were any differences between the groups (micro/small and medium/large). The ANOVA showed that there were no significant differences between the groups.

With the purified database, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were applied to confirm the model, which contains the relationships between the variables in each construct. To do this, Version 20 of the SPPS software was used for support. It generated a report suggesting factors (EFA) that explained 63.58% of the variability in the data. This test of the empirical data confirmed the grouping of the observable variables into factors (latent variables), which are presented in Table 2. Eliminating factorial loads lower than 0.4 (Hair Jr. et al., 2009), the Varimax rotation confirmed the model proposed for creating factors.

The analysis of the consistency of the real load measurements was used to analyze the composite validity of the constructs. In this study, the constructs were above the ideal value (0.70). Though this number is not a standardized norm of conduct (Marôco, 2010) this evaluation helps in the analysis of the model's measurement and reliability. The composite reliability test presented the following results: i) environmental management (0.94), ii) social responsibility (0.95) and iii) organizational performance (0.91). Cronbach's alpha was used to verify the internal consistency of the dimensions in the questionnaire, for which Hair Jr. et al. (2009) recommend a minimum value of 0.7. This study found the following Cronbach's alpha values: i) environmental management (0.897), ii) social responsibility (0.917) and iii) organizational performance (0.852). The KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) test allowed for verification of the correlations between the variables, providing the statistical probability of significant correlations between the measurable variables. A KMO value of 0.906 was obtained, which shows that factorial analysis is appropriate for examining the data.

The proposed model (Figure 1) graphically represents the hypotheses formulated based on the bibliographic study. In the empirical test of this model, an individual validation of each construct was performed through the identification of the estimated coefficients of each observable variable, considering their capacity to measure the latent variable (Hair Jr. et al., 2009).

Table 2 presents the chi square distribution for RMSEA, AGFI, NFI, GFI and CFI, which contributed to the analysis of the research results through SEM. In the chi square tests (AMOS™) the proposed model was shown to be significant (<0.001), indicating that there is a difference between the observed matrix and the estimated matrix (Hair Jr. et al., 2009). Another important analysis for determining the level of significance is the observation of the chi square relationship (χ2) divided by the degrees of freedom (DF), obtaining a 2.67 value, for which (Tanaka, 1993) consider values less than or equal to 5 acceptable.

The analysis of the RMSEA indicator represents the difference between the observed and estimated matrix, for which the recommended value is between 0.05 and 0.08 (Hair Jr. et al., 2009). The analysis of the data presented a 0.08 value, the highest number recommended. This result demonstrated that the proposed model is adequate for evaluating the situation found at the companies being studied, therefore justifying maintaining the observable variables and proposed correlations.

To validate the constructs, the CFA was used to assess the proposed model, which integrates i) the measurement model and ii) the structural model (Hair Jr. et al., 2009). Consequently, the relationships between the Environmental Management, Social Responsibility and Organizational Performance constructs were measured. These constructs are formed by observable variables, which are evaluated in the CFA phase. The model evaluation was done based on the adjustment rates and the statistical significance of the estimated regression coefficients (Kline, 2010; Byrne, 2009). The numbers shown in Table 2 (CFI, GFI, NFI and AGFI) are comparative adjustment measures, which aim to compare the proposed model and the null model (Blunch, 2012). The values calculated show good adjustment for the model, because these results are within the recommended limit (0.9) (Hair Jr. et al., 2009) or very close to it. Thus, the analysis model is considered adequate for this empirical study. The covariance in Table 3 and the correlations in Table 4 present the test of the hypotheses, showing that the correlations between the constructs are significant.

Índice |

Integrated model final |

Chi-square |

445.890 |

Degree of freedom (DF) |

167 |

Chi-square divided by the Degree of freedom |

2.67 |

Level of probability |

0,000* |

KMO - Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy |

0.906 |

CFI - Comparative Fit Index |

0.904 |

NFI – Normed Fit índex |

0.855 |

GFI – Goodness of Fit Index |

0.844 |

AGFI - Adjusted Goodness of Fit |

0.804 |

RMSEA - Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation |

0.080 |

Confiabilidade Composta |

0.977 |

Composed confiability |

0.686 |

Cronbach's Alpha |

0.926 |

Table 2 – Adjustment index of the integrated model

Source: Research Data from the AMOS report.

Constructs |

|

|

Standardized |

Standard Deviation |

C.R. |

p |

Environmental Management |

<--> |

Social Responsibility |

0,471 |

0,077 |

6,104 |

*** |

Social Responsibility |

<--> |

Organizational performance |

0,356 |

0,072 |

4,982 |

*** |

Environmental Management |

<--> |

Organizational performance |

0,266 |

0,053 |

5,002 |

*** |

Constructs |

|

|

Estimate |

Environmental Management |

<--> |

Social Responsibility |

0,668 |

Social Responsibility |

<--> |

Organizational performance |

0,400 |

Environmental Management |

<--> |

Organizational performance |

0,444 |

Table 4 – Testing of hypotheses (correlation)

Source: Research Data from the AMOS report.

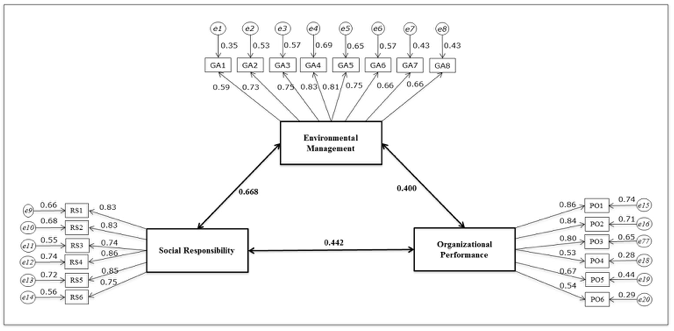

An analysis of the results confirmed all of the hypotheses (H1, H2 and H3) (Figure 2). Therefore, the companies in the AMMC of Serra Gaúcha present a positive correlation between environmental management and social responsibility (H1), which reinforces Elkington's (1999) assertions that environmental management and social responsibility are pillars of sustainability. The findings highlight that respecting human beings and the environment are among the main factors that directly affect organizational success (Grayson; Hodges, 2004; Porter; Kramer, 2002; Seiffert, 2008; David et al., 2013).

Figure 2 – Final Model Search

Source: Authors (2016).

H2 proposes that environmental management is positively correlated with organizational performance. The results demonstrate that environmental management aims to diminish the consumption of inputs and raw materials, reduce production costs, reduce waste, lessen environmental impacts and encourage increases in productivity and competitiveness (Halkos; Evangelinos, 2002; Molina-Azorín et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2012; Kassinis; Soteriou, 2003; Buysse; Verbeke, 2003; Handfield et al., 2003; Gonzalez-Benito; Gonzalez-Benito, 2005; Iraldo et al., 2009; Crowe; Brennan, 2007; Yang et al., 2010), showing that there is a positive correlation between adopting environmental management practices and organizational performance.

H3 proposes that social responsibility is positively correlated with organizational performance. In this regard, the results of the research refute the Griffin and Mahon (1997) study that claimed there was no strong, existing consensus on the relationship between social responsibility and organizational performance, because results were often contradictory. On the other hand, the findings corroborate the studies done by Graves and Waddock (1994), Preston and O'Bannon (1997), Roman et al. (1999) and Simpson and Kohers (2002), as they show that organizational performance influences social responsibility and vice-versa, and there is a synergistic relationship between the two.

The northeastern region in the state of Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) is home to the Serra Gaúcha AMMC, which is the second largest automotive metal-mechanics cluster in Brazil, due to the large concentration of companies from the sector, which generates important revenues for the state and regional economy. These companies, which were initially motivated by legal issues, developed environmental management programs and implemented social responsibility initiatives. This study analyzed the correlation between environmental management and social responsibility, as well as their correlation with organizational performance, taking into account the different studies in the literature that support the hypotheses in this study.

One of the main highlights in the research is the validation of the metrics for the constructs, reinforcing the assertions of Instituto Ethos (2013), Gri (2013), Severo (2013) and Paladino (2007), while the reliability of the observable variables contributed to the understanding of the constructs (environmental management, social responsibility and organizational performance). These metrics give the world of academia a framework for analyzing socio-environmental issues and their connections to company performance.

The contribution of this study to the business world is in its statistical results, which prove that environmental management and social responsibility are positively correlated with organizational performance. Therefore, companies that implement socio-environmental initiatives and programs present superior organizational performance when compared to companies that present few or no initiatives in the social and environmental areas. These managerial implications are a key economic incentive argument for business people and investors in the automotive metal-mechanics industry.

It is important to note that the study analyzed a 9.2% sample of the total Serra Gaúcha AMMC population, reflecting only the perceptions of the respondents at the companies being studied. This means that future studies should analyze the correlation between the environmental management, social responsibility and organizational performance constructs at other companies in Brazil. New studies should include comparative analyses between various business sizes and different industrial sectors. Though scientific rigor was used in the execution of this research, there are methodological limitations related to the non-probability sampling technique.

AGBOOLA, J. I. (2014); "Technological innovation and developmental strategies for sustainable management of aquatic resources in developing countries". Environmental Management, 54 (6), 1237-1248.

ARAGÓN-CORREA, J. A. (1998); "Strategic proactivity and firm approach to the natural environment". Academy of Management Journal, 41, 556-567.

ARAGÓN-CORREA, J. A.; HURTADO-TORRES, N.; SHARM, S.; GARCÍA-MORALES, V. J. (2008); "Environmental strategy and performance in small firms: a resource-based perspective". Journal of Environmental Management, 86, 88-103.

BARNEY, J. B. (2013); Gaining and sustaining competitive advantage. 5 ed., New Jersey: Pearson New International Edition.

BENTLER, P. M. (1990); "Comparative fit indexes in structural equations". Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238-246.

BLUNCH, N. J. (2012); Introduction to structural equation modeling using IBM SPSS Statistics and Amos. 2 ed., London: SAGE Publications.

BRASIL. Pnma – Política Nacional de Meio Ambiente. (2000); Lei nº 10.165 de 27 de dezembro de 2000. Brasília – DF. Retrieved from <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Leis/L10165.htm>. Accessed: 20 Jul. 2013.

BUYSSE, K.; VERBEKE, A. (2003); "Proactive environmental strategies: a stakeholder management perspective". Strategic Management Journal, 24, 453-470.

BYRNE, B. M. (2009); Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications and programming. 2 ed., New York: Routledge.

CLAVER, E.; LÓPEZ, M. D.; MOLINA, J. F.; TARI, J. J. (2007); "Environmental management and firm performance: a case study". Journal of Environmental Management, 84, 606-619.

CROWE, D.; BRENNAN, L. (2007); "Environmental considerations within manufacturing strategy: an international study". Business Strategy and The Environment, 16, 266-289.

DARNALL, N.; JOLLEY, G. J.; HANDFIELD, R. (2008); "Environmental management systems and green supply chain management: complements for sustainability?" Business Strategy and the Environment, 17(1), 30-45.

DAVID, F.; ABREU, R.; PINHEIRO, O. (2013); "Local action groups: Accountability, social responsibility and law". International Journal of Law and Management, 55(1), 5-27.

ELKINGTON, J. (1999); Cannibals with forks. Canada: New Society.

FIERGS, Federação das Indústrias do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. (2011); Cadastro Industrial do Rio Grande do Sul 2011. CDROM.

GONZALEZ-BENITO, J. G.; GONZALEZ-BENITO, O. G. (2005); "Environmental proactivity and business performance: an empirical analysis". Omega – The International Journal of Management Science, 33(1), 1-15.

GONZALEZ-BENITO, J. G.; GONZALEZ-BENITO, O. G. (2006); "A review of determinant factors of environmental proactivity". Business Strategy and the Environment, 15, 87-102.

GRAVES, S. B.; WADDOCK, S. A. (1994); "Institutional owners and corporate social performance". Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1034-1046.

GRAYSON, D., HODGES, A. (2004); Corporate social opportunity: seven steps to make corporate social responsibility work for your business. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

GRI, Global Reporting Initiative. (2013); Retrieved from <https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/G3.1-Sustainability-Reporting-Guidelines.pdf>. Accessed: 20 Jul. 2013.

GRIFFIN, J.; MAHON, J. (1997); "The corporate social performance and corporate financial performance debate". Business & Society, 36(1), 5-32.

GUIMARÃES, J. C. F.; SEVERO, E. A.; DORION, E. C. H. (2014); "Cleaner Production and Environmental Sustainability: multiple Case From Serra Gaúcha – Brazil". Espacios (Caracas), 35 (4), 8.

GUIMARÃES, J. C. F.; SEVERO, E. A.; DORION, E. C. H.; OLEA, P. M. (2015); "Attributes for sustainable competitive advantage of firms in the global market". Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 9 (7), 459-468.

GUNAWAN, J. (2007); "Corporate social disclosures by Indonesian listed companies: a pilot study". Social Responsibility Journal, 3(3), 26-34.

HAIR Jr., J. F.; BLACK, W. C.; BARBIN, B.; ANDERSON, R. E. (2009); Multivariate data analysis. 7 ed., New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

HALKOS, G. E.; EVANGELINOS, K. I. (2002); "Determinants of environmental management systems standards implementation: evidence from Greek industry". Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(6), 360-375.

HANDFIELD, R.; SROUFE, R.; WALTON, S. (2005); "Integrating environmental management and supply chain strategies". Business Strategy and the Environment, 14(1), 1-19.

HENRY, M.; KATO, Y. (2011); "An assessment framework based on social perspectives and analytic hierarchy process: a case study on sustainability in the Japanese concrete industry". Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 28, 300-316.

HOFMANN, K.H.; THEYEL, G.; WOOD, C. H. (2012); "Identifying firm capabilities as drivers of environmental management and sustainability practices - evidence from small and medium-sized manufacturers". Business Strategy and the Environment, 21(8), 530-545.

IBGE, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2013); Retrieved from <http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/indicadores_sociais_municipais/default_indicadores_sociais_municipais.shtm>. Accessed: 10 Jun. 2013.

INSTITUTO ETHOS. (2013); Indicadores Ethos 2ª Geração. Retrieved from <http://www3.ethos.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/IndicadoresEthos_2013_PORT.pd>. Accessed: 10 Jun. 2013.

IRALDO, F.; TESTA, F.; FREY, M. (2009); "Is an environmental management system able to influence environmental and competitive performance? The case of the ecomanagement and audit scheme (EMAS) in the European Union". Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(16), 1444-1452.

ITTIPANUVAT, V.; FUJITA, K.; SAKATA, I.; KAJIKAWA, Y. (2014); "Finding linkage between technology and social issue: a literature based discovery approach". Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 32, 160-184.

JABBOUR, C. J. C.; TEIXEIRA, A. A.; JABBOUR A. B. L. S.; FREITAS, W. R. S. (2012); "Verdes e competitivas? A influência da gestão ambiental no desempenho operacional de empresas brasileiras". Ambiente & Sociedade, 15(2), 151-172.

KASSINIS, G. I.; SOTERIOU, A. C. (2003); "Greening the service profit chain: the impact of environmental management practices". Production and Operations Management, 12(3), 386-403.

KLINE, R. B. (2010); Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3 ed., New York: The Guilford Press.

KLUGA, H.; KMOCH, A. (2015); "Operationalizing environmental indicators for real time multi-purpose decision making and action support". Ecological Modelling, 295, 66-74.

LI, Y. P.; HUANG, G. H.; YANG, Z. F. (2009); "IFTCIP: An Integrated Optimization Model for Environmental Management under Uncertainty". Environmental Modeling & Assessment, 14(3), 315-332.

LIN, R. J.; TAN, K. H.; GENG, Y. (2012); "Market demand, green product innovation, and firm performance: evidence from Vietnam motorcycle industry". Journal of Cleaner Production, 30, 1-7.

MAHONEY, L.; ROBERTS, R. W. (2002); Corporate social and environmental performance and their relation to financial performance and institutional ownership: empirical evidence on Canadian Firms. Working Paper. University of Central Florida. Kenneth: G. Dixon School of Accounting.

MARDIA, K. V. (1971); "The effect of nonnormality on some multivariate tests and robustness to nonnormality in the linear model". Biometrika, 58(1), 105-121.

MARÔCO, J. (2010); Análise de equações estruturais: fundamentos teóricos, softwares & aplicações. Lisboa: PSE.

MATTILA, M. (2009); "Corporate social responsibility and image

in organizations: for the insiders or the outsiders?" Social Responsibility Journal, 5(4), 540-549.

MOLINA-AZORÍN, J. F.; CLAVER-CORTÉS, E.; PEREIRA-MOLINER, J.; TARÍ, J. J. (2009); "Environmental practices and firm performance: an empirical analysis in the Spanish hotel industry". Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(5), 516-524.

MORRISON, C.; ROUNDS, I.; WATLING D. (2012); "Conservation and management of the endangered Fiji Sago Palm, Metroxylon vitiense, in Fiji". Environmental Management, 49(5), 929-941.

MÖRTBERGA, U. M.; BALFORSA, B.; KNOL, W. C. (2007); "Landscape ecological assessment: A tool for integrating biodiversity issues in strategic environmental assessment and planning". Journal of Environmental Management, 82, 457-470.

NGAI, E. W. T.; CHAU, D. C. K.; LO, C. W. H.; LEI, C. F. (2014); "Design and development of a corporate sustainability index platform for corporate sustainability performance analysis". Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 34, 63-77.

NIKOLAOU, I. E.; CHYMIS, A.; EVANGELINOS, K. (2013); "Environmental information, asymmetric information, and financial markets: a game-theoretic approach". Environmental Modeling & Assessment, 18(6), 615-628.

PALADINO, A. (2007); "Investigating the drivers of innovation and new product success: a comparison of strategic orientations". Journal of Product Innovation Management, 24, 534-553.

PORTER, M. E., KRAMER, M. R. (2002); "The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy". Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 56-68.

POTTS, T. (2010); "The natural advantage of regions: linking sustainability, innovation, and regional development in Australia". Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(8), 713-725.

PRESTON, L. E.; O'BANNON, D. P. (1997); "The corporate social-financial performance relationship". Business & Society, 36(4), 419-429.

ROMAN, R. M.; HAYIBOR, S.; AGLE, B. R. (1999); "The relationship between social and financial performance: Repainting a portrait". Business & Society, 38(1), 109-125.

RUF, B. M.; MURALIDHAR, K.; BROWN, R. M.; JANNEY, J. J.; PAUL, K. (2001); "An empirical investigation of the relationship between change in corporate social performance and financial performance: a stakeholder theory perspective". Journal of Business Ethics, 32, 143-156.

SEIFFERT, M. E. B. (2008); "Environmental impact evaluation using a cooperative model for implementing EMS (ISO 14001) in small and medium-sized enterprises". Journal of Cleaner Production, 16, 1447-1461.

SEVERO, E. A. (2013); Inovação e sustentabilidade ambiental nas empresas do arranjo produtivo local metalmecânico automotivo da Serra Gaúcha. Tese (Doutorado em Administração) Programa de Pós-Gradução Doutorado em Administração, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul/Universidade de Caxias do Sul, 2013.

SEVERO, E. A.; GUIMARÃES, J. C. F. (2015); "Corporate environmentalism: an empirical study in Brazil". International Journal Business and Globalisation, 15(1), 81-95.

SEVERO, E. A., GUIMARÃES, J. C. F., DORION, E. C. H., NODARI, C. H. (2015); "Cleaner production, environmental sustainability and organizational performance: an empirical study in the Brazilian metal-mechanic industry". Journal of Cleaner Production, 96, 118-125.

SHARMA, S. (2000); "Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy". Academy of Management Journal, 43, 681-697.

SIMECS, Sindicato das Indústrias Metalúrgicas, Mecânicas e de Material Elétrico de Caxias do Sul. (2013); Retrieved from: <http://www.simecs.com.br/empresas-do-simecs/resultados-economicos.asp>. Accessed: Jul. 15. 2013.

SIMPSON, W. G.; KOHERS, T. (2002); "The link between Corporate social and financial performance: Evidence from the Banking Industry". Journal of Business Ethics, 35(2), 97-109.

STOUGH-HUNTER, A.; LEKIES, K. S. DONNERMEYER, J. F. (2014); "When environmental action does not activate concern: the case of impaired water quality in two rural watersheds". Environmental Management, 54(6), 1306–1319.

TANAKA, J. S. (1993); Multifaceted conceptions on fit in structural equations modeling. In: BOLLEN, K. A.; LONG, J.S. (Eds.). Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park: Sage, 10-39.

WELCH, E. W.; MORI, Y.; AOYAGI-USUI, M. (2002); "Voluntary ad option of ISO 14001 in Japan: mechanisms, stages and effects". Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(1), 43-62.

WU, E. M.-Y.; TSAI, C. C.; CHENG, J. F.; KUO, S. L.; LU, W. T. (2014); "The application of water quality monitoring data in a reservoir watershed using AMOS confirmatory factor analyses". Environmental Modeling & Assessment, 19(4), 325-333.

YANG, C.; LIN, S.; CHAN, Y.; SHEU, C. (2010); "Mediated effect of environmental management on manufacturing competitiveness: an empirical study". International Journal of Production Economics, 123, 210-220.

YORK, R.; ROSA, E. A.; DIETZ, T. (2003); "Footprints on the earth: the environmental consequences of modernity". American Sociological Review, 68(2), 279-300.

ZHOU, X.; NIXON, H.; OGUNSEITAN, O. A.; SHAPIRO, A. A.; SCHOENUNG J. M. (2011); " Transition to lead-free products in the us electronics industry: a model of environmental, technical, and economic preferences". Environmental Modeling & Assessment, 16(1), 107-118.

1. Doutora em Administração. Programa de Pós-Graduação Mestrado em Administração. Faculdade Meridional (IMED) – Brasil – elianasevero2@hotmail.com

2. Doutor em Administração. Programa de Pós-Graduação Mestrado em Administração. Faculdade Meridional (IMED) – Brasil –juliocfguimaraes@yahoo.com.br

3. Doutor em Administração. Professor de Graduação. Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing (ESPM) – Brasil – claudiorottabr@gmail.com