HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN

HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN Espacios. Vol. 37 (Nº 03) Año 2016. Pág. 12

Deosir Flávio Lobo de CASTRO JÚNIOR 1; Marcelo Augusto Menezes DELUCA 2; Márcio Nakayama MIURA 3; Elvis SILVEIRA-MARTINS 4; Anderson Antonio Mattos MARTINS 5; Renata SILVERIO 6

Recibido: 16/09/15 • Aprobado: 15/11/2015

4. Analysis and discussion of the data

ABSTRACT: The society presents a number of demands that organizations try to fulfill. To achieve the goal of delivering value and satisfaction to society, the involvement of several actors who play their individual roles becomes necessary, in order to identify the main stakeholders, participants in the market of organic Fruits and Vegetables (FLV) in Florianopolis/Brazil, and examine which factors boost and constrain this activity. This research was conducted following the empirical, exploratory, and descriptive approaches. The object of analysis of this research is delimited to the key stakeholders identified in Florianopolis, with respect to production of organic FLV. The selection of interviewees was made by convenience, identified as: i) CEASA; ii) EPAGRI; iii) NGOs; iv) Conventional producers; v) Organic Producers; and vi) current and potential consumers. Semi-structured interviews were the main source of data collection. The interview script used was drawn from the stakeholder theory, by Freeman (1984). As a result of this research, we highlight the absence of an agent, the Corporate Governance, with Management Capacity of Stakeholders. There is the need to manage the relationship with groups of specific interest, in an action-oriented manner, towards mutual benefits. |

RESUMO: A sociedade apresenta uma série de demandas, que as organizações buscam atender. Para a consecução deste, entregar valor e satisfação para a sociedade, se faz necessário à participação de diversos atores, que desempenham cada qual o seu papel. Com o objetivo de identificar os principais stakeholders, partícipes do mercado de Frutas, Legumes e Verduras (FLV) orgânicos na Grande Florianópolis, e verificar quais os fatores que impulsionam e restringem esta atividade. Para a realização da presente pesquisa, foram percorridos os seguintes caminhos metodológicos, pesquisa empírica, pesquisa exploratória, pesquisa descritiva, a unidade de análise desta pesquisa delimita-se nos principais stakeholders identificados na Grande Florianópolis, no que tange ao tema FLV orgânicos. A seleção dos sujeitos entrevistados foi por conveniência, identificadas, como: i) CEASA; ii) EPAGRI; iii) ONG; iv) Produtores Convencionais; v) Produtores Orgânicos; e vi) Consumidores atuais e potenciais. A principal fonte de coleta de evidências aplicada neste estudo foram as entrevistas semiestruturadas. O roteiro das entrevistas, utilizado na pesquisa, foi elaborado a partir da teoria dos stakeholders, Freeman (1984). Como resultado desta pesquisa, destaca-se a ausência de um agente, a Governança Corporativa; com Capacidade de Gestão dos Stakeholders. Existindo a necessidade de em gerenciar o relacionamento com seus grupos de interesse específicos, de uma forma orientada para a ação, e benefícios mútuos. |

According to Ribeiro et al. (2014), the term stakeholder first emerged in the administrative field in an internal memo of the Stanford Research Institute in 1963. In the 1980s, this terminology was disseminated in academia from Freeman and Reed's (1983) work, leading to maturation and recently a consolidation of the theory of stakeholders (TS).

Vieira et al. (2011) state that the issue of stakeholders has been discussed in the management literature since the publication of Richard E. Freeman in 1984, and the management of stakeholders is repeatedly highlighted as a critical success factor. Freeman (1984) reports that the stakeholder theory is one in which the organization's effectiveness is measured by its ability to satisfy not only shareholders, but also those agents that have a link with the organization.

According to Lyra, Gomes, and Jacovine (2009) stakeholder is, by definition, any group or individual who can affect or be affected by the achievement of the objectives of a company (FREEMAN, 1984). Stakeholder includes all individuals, groups and other organizations that have an interest in the assets and in the marketing plan of a particular company, and that have the ability to influence it (SAVAGE; NIX; WHITEHEAD; BLAIR, 1991).

Pavão et al. (2012) highlight the study Shropshire and Hillmann (2007), which seeks to understand how companies have significant experience in managing stakeholders. A significant contribution, however, is the work of Agle et al. (2008) who resume several studies termed as Dialogue: Toward Superior Stakeholder Theory. The main focus is that now the issue is not one of if, but of how the theory of stakeholders will face the challenges of its success.

Lyra, Gomes, and Jacovine (2009) emphasize that an expansion of collective consciousness with respect to the environment and to its complexity in today's environmental demands that society passes on to organizations, leads to a new position by firms that are responsible for such issues (TACHIZAWA, 2002). Also in this sense, the search of procedures, mechanisms and arrangements in behavioral standards developed by organizations defines those companies that are more or less competent in responding to the aspirations of society (DONAIRE, 1999).

Knorek (2011) states that the existence of constant changes arising in the process of economic development in recent decades is characterized, in a way, by instability and increase in market competitiveness, especially when projects are developed with partners to leverage growth and development of a given territory or region. Knorek further states that agricultural activities, especially in the plateau region of the north of Santa Catarina, have a reality of multiple difficulties, both in the social sphere as in the economic, and thus everything is conducive to the difficulty of production, processing and marketing of goods produced by small farmers in the region.

According to Silva and Lourenzani (2011), horticulture is characterized in two important respects: i) it is intensive in labor and ii) it has reduced minimum scale of production so that the activity is profitable. From these characteristics, horticulture FLV becomes an alternative for small producers as well as for family farming. Horticulture also stands out for being a great field labor booster, helping to prevent rural migration problems and to improve the distribution of income. Mello and Schmidt (2002), while researching the family farming in Western Santa Catarina, said that in 2002, in this region there were just over 88,000 agricultural establishments, and 70.08% of them had an area less than 20 hectares, and 93.84 % of them had an area less than 50 hectares.

Fernandes and Karnopp (2014) show that in the reality of family farming, as opposed to the conventional model, the organic production model is gaining new adherents. This practice aims to develop healthy and sustainable eating habits in order to minimize the impacts to ecosystems and to ensure fertile soil and water quality. To achieve these, we must analyze the production chain.

Given the above context, this work aims to identify the main stakeholders of organic FLV in Florianopolis, and identify factors that boost and constrain the sector.

The concept of organic food production is defined by IFOAM - Organics International Action Group (2013) as a method for production of food developed from its most basic state through a process of improvement, breeding and advancement in the techniques employed in the use of natural resources in a sustainable manner.

Lima (2014) points out that organic foods do not mean foods produced without pesticides. Concepts may be used by researchers when defining what would be an organic food. For the author, the purpose of the production of organic food is to provide the population with the availability of healthy products, promote the healthy use of water, soil and air, while maintaining soil fertility for a longer period of time. This is made possible by the recycling of organic waste, and the fostering of the integration of different segments of the production chain and consumption of organic products.

Anacleto, Paladini and Campos (2014) present the organic agriculture as a reaction to the introduction of toxic chemical fertilizers by agrochemical industries due to the industrialization of agriculture and, in a way, the growing environmental awareness in society at large (Torjusen, Lieblein, and VITTERSO, 2001).

Conventional agriculture gradually undermines the ecosystem's ability to provide essential services for the survival of the human race, changing or aiding to change the climate, leading to water and soil pollution, loss of biodiversity and the depletion of natural resources (KAUFMANN, STAGL ; FRANKS, 2009).

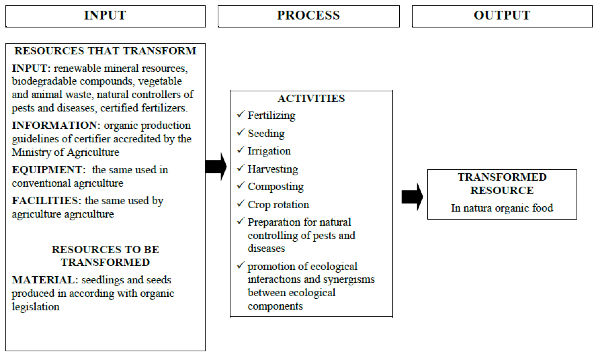

Figure 1. Vision of the organic agriculture process

Source: Anacleto, Paladini, e Campos (2014, p. 503, our translation)

Caswell (2000, cited in Anacleto, Paladini and Campos, 2014) points out that, to achieve the quality of organic food in terms of product, farmers are guided by the questions: i) food security attributes: monitoring of the level of some substances that are detrimental to food security, for example, residues of pesticides, pathogens, heavy metals, additives, toxins and veterinary waste; ii) Nutrition attributes: fat, calories, fiber, sodium, vitamins and minerals; iii) value attributes: purity, composition integrity, size, appearance, taste, convenience of preparation; iv) Packaging Attributes: packaging material, labeling and other information; v) Production process attributes: animal welfare present in farm, genetic modification, environmental impact, use of pesticides in the production, worker safety.

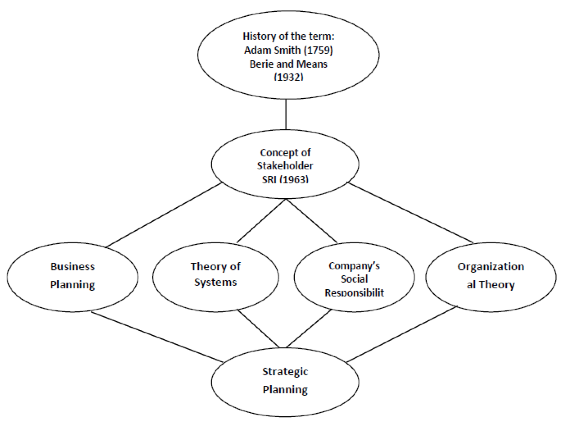

Pavão et al. (2012) present as a primary definition of the term stakeholder (a definition which has now been consolidated) as an individual or group of individuals that can affect or be affected by the objectives proposed by the organization. This group should include the producers/workers, clients/customers, suppliers, shareholders (or stockholders), banks/financers, environmentalists, government and other groups that can help or constrain the organization. The history of the concept of stakeholders was presented by Freeman (1984) and is represented graphically (Figure 2) following its chronology, formed by the authors of this seminal issue in academia.

Figure 2. History if the concept of Stakeholders

Source: Pavão et al. (2012) Adapted from figure presented by Freeman (1984, p.32, our translation).

Goldschmidt (2010) advocates that organizations involve stakeholders in their actions with the following objectives: i) to identify the demands of the relevant public since these have more knowledge regarding the company's shares; ii) to facilitate the obtaining of information in internal and external environment for better decision-making; iii) to manage consensus with respect to differing opinions; iv) to improve understanding of threats and opportunities by checking reviews of people from the external environment of the organization; v) to build confidence between the company and its stakeholders.

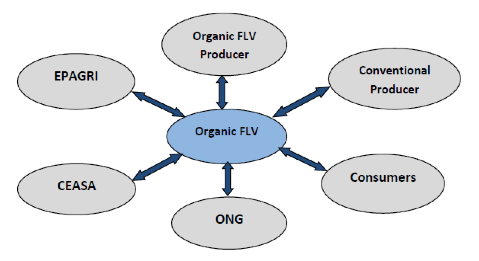

Savitz (2007) maintains that in order to understand the stakeholders two actors can be identified, internal and external. Internal stakeholders are employees, the value chain stakeholders, suppliers and consumers; external stakeholders are communities, investors, NGOs, government agencies, regulators, media - and even the future generations who may be affected by the company's performance. The conceptual map of stakeholders of this study was developed following these guidelines.

Figure 3 – Conceptual map of Stakeholders of Organic FLV of Florianopolis

Source: developed by the authors

In this study, the stakeholders of organic FLV process in Florianopolis were identified as follows: internal stakeholders are organic farmers and traditional producers, value chain stakeholders, and consumers of FLV; external stakeholders are NGOs, government and regulatory bodies, CEASA and EPAGRI.

Freeman (1984) presents the dimensions and prescriptive concepts of the propositions of stakeholders. Pavão et al. (2012), elaborated from the description, a framework that aids comprehension.

Table 1. Business propositions

Dimensions |

Prescriptive Concepts |

Communication Process |

Organizations with high CGS design and implement communication processes with multiple stakeholders |

Negotiation

|

Organizations with high CGS negotiate explicitly with stakeholders on critical questions and seek voluntary agreements |

Marketing

|

Organizations with high CGS spread and approximate marketing to serve multiple stakeholders. |

Strategic formulation |

Organizations with high CGS integrate key limits in the process of strategic formulation in the organization |

Proactivity

|

Organizations with high CGS are proactive – They anticipate concerns with stakeholders and attempt to influence stakeholders' environment. |

Resources

|

Organizations with high CGS coherently allocate resources with stakeholders' concerns. |

Stakeholder serving |

Managers of organizations with high CGS think in terms of how to serve their stakeholders. |

Source: Pavão et al. (2012). Elaborated based on the description realized by Freeman (1984, p.78-80).

Freeman, Harrison and Wicks (2007) associated the CGS with the company's routines/activities (Business, Processes and Capabilities) and the concern for creating value for stakeholders. The terms communication and negotiation were associated, considering the conceptual similarity between them, as described in the following: i) Communication and negotiation - Organizations with high CGS design and implement communication processes with multiple stakeholders, and explicitly negotiate with stakeholders on critical issues and seek voluntary agreements; ii) Marketing - Organizations with high CGS extend the marketing approach to serve multiple stakeholders. They use marketing techniques in order to better understand the needs of stakeholders, and utilize marketing research as a tool to understand the majority of stakeholder groups; iii) Strategy Formulation - Organizations with high CGS break barriers (boundary spanners). Many organizations have public relations or public relations managers who have a good knowledge of the concerns of stakeholders, and have production and marketing managers who have experience in customer and supplier needs. However, these managers do not always form part of the strategic planning process. The assumption is that these managers who have an obligation to be sensitive to the needs of stakeholders are best placed to represent their interests within the organization; iv) Proactive - Organizations with high CGS are proactive - They anticipate the concerns of stakeholders and try to influence their environment – for example, the micro-computer industry is full of companies that have a policy of anticipation in order to survive. These companies, some of them very small, try to spend resources to figure out what could best serve the customer in the future; v) Resources - Organizations with high CGS consistently allocate resources to meet the concerns and needs of its stakeholders - The author refers to Emshoff (1980) who speaks of stakeholder analysis in a large international company and the ranking of stakeholders in order of importance. He adds that it was found how the company's resources were allocated to deal with those groups that would be most important in the future. The results of his research indicate that resources have not been allocated to deal with these groups that would be crucial to the success of the company, or were not a priority; vi) Stakeholder-serving - Managers of organizations with high CGS think in terms of how to serve their stakeholders - the author states that just as many successful companies think in terms of "how to serve the customer" or "how to serve employees"; it is possible to generalize this philosophy to "how to serve my stakeholder". The "rationale" for most organizations is that they serve some need in their external environment. When an organization loses its sense of purpose and mission, or when it is internally focused on the needs of their managers, it will risk becoming irrelevant. Someone (possibly a competitor) will best suit the needs of the environment. (PAVÃO et al., 2012).

This work is characterized as an exploratory, descriptive and qualitative research. With regard to the purposes, the exploratory research investigated the factors that boost or constrain the production and consumption of organic FLV in Florianopolis. The research is also descriptive because, after lengthy investigation, we described the reality found in the context of organic FLV in Florianopolis. It is qualitative in regards to the procedures used.

The object of analysis of this research is delimited to the key stakeholders identified in Florianopolis, with respect to organic FLV. The selection of interviewees was made by convenience, that is, by their participation in one or more of the identified roles. Not following an order of importance, we identified the subjects as: i) CEASA (SC); ii) EPAGRI / SC; iii) NGOs; iv) Conventional Producers of Florianopolis, which use chemicals in their process; v) Organic Producers of Florianopolis; vi) current and potential consumers of organic products.

The field research was divided into two phases. In the initial phase, emphasis was given to organizations and producers, and ultimately to consumers. The main source of evidence collection that was used in this study was semi-structured interviews with open questions, conducted individually or in groups, face to face with the selected subjects (CEASA, EPAGRI, Manufacturers Conventional and Organic Producers). With current and potential consumers we used the focus group technique.

The interview script used in the survey was drawn from the theory of stakeholders (Freeman, 1984), though, leaving room to explore new visions and perceptions. Each interview was scheduled in advance and in person at the headquarters of the organizations. Permission was requested to use voice recorder. Each interview lasted between 90 and 120 minutes, went through a verbatim transcription, and was analyzed in accordance with the criteria of booster or constraining for organic FLV.

In CEASA/SC the interviewee was the CEO of the agency. In EPAGRI the respondent was the agribusiness manager who is an agronomist. The NGO was chosen for being the only supplier of organic FLV products within the CEASA of Santa Catarina.

The conventional producer is called Antônio Carlos and is in the business of producing and selling FLV since the 1980s, but as he says, "you know that I've always been in the field? I was born here."

The organic farmer has a property located in Santo Amaro da Imperatriz and is one of the largest organic FLV producers in the region. He produces FLV since 1995 and has been working with organic products since 2008, when due to a personal illness by chemical contamination of pesticides he decided to start organic production, with a view to improving his own health.

With current and potential consumers we performed the focus group technique. Consumers were selected from residents of the Trindade neighborhood, city of Florianopolis – SC, and based on the work of Kind (2004, p.125) that defines the focus group as a group interview which serves specific purposes in a given investigation. For the author, the focus group makes use of group interaction for data production and insights, and is considered an appropriate data collection technique for qualitative research.

Eight residents of the Trindade neighborhood were selected based on their willingness to participate, and because they fit the required profile: to be of legal age and the main FLV buyer of the house. Furthermore, a criterion was also adopted that at least two respondents were usual buyers of organic FLV. The work was carried out on a commercial, easily accessible area, with all the features that facilitate the process: absence of noise, privacy, and comfort (KIND 2004).

The process, as a whole in each of the condos, lasted about two hours with a 20 minute coffee break. Only in one case, one of the interviewees had to stop for about 30 minutes in the process. However this only occurred at the end of the work, causing no harm to his participation.

Table 2: Profile of respondents and focus group participants

Classification |

Sex |

Age |

Profession |

Organic? |

Code |

Consumer |

F |

30 |

Student |

Yes |

C1 |

Consumer |

M |

29 |

Teacher |

Yes |

C2 |

Consumer |

M |

45 |

FP |

No |

C3 |

Consumer |

F |

33 |

FP |

No |

C4 |

Consumer |

M |

58 |

DC |

No |

C5 |

Consumer |

F |

26 |

Secretary |

Yes |

CC1 |

Consumer |

F |

28 |

Businesswoman |

Yes |

CC2 |

Consumer |

M |

52 |

Organic Chef |

Yes |

CC3 |

NSE – Does not fit; FP – Public Official; DC – Housewife; M – Male; F – Female

Fonte: Research data

Table 2 presents the characteristics of all respondents and focus group participants targeted in this research, and the codes used to designate each. The observer and the moderator of the technique used (focus group) are part of the group of researchers and have doctorate and master's degrees in administration, respectively, and long experience in teaching and in conducting research projects.

We have, therefore, a way to go weaving an interpretation and analysis, from different perspectives and respecting the possible differential positions underlying the interviews worked in this study. From the content analysis of the interviews and the perception of researchers, we present in the following sections the analysis and discussion of the data.

Based on a semi structured questionnaire we interviewed the segments of stakeholders identified in the process and analyzed them in accordance with the criteria of booster or constraining of organic FLV. In the sequence, we present the analysis of the interviews, in which we adopt the initial codes to designate respondents and focus group participants, following the order of interviews and focus groups conducted: CEASA, EPAGRI, NGOs, Conventional Producers, Organic Producer, Condo Residents 1, and Condo Residents 2.

The meeting was scheduled directly with the respondent (designated as CE-SC) by phone, with a week in advance, and information relating to the interview content was also provided in this call. The interview took place in CEASA-SC office, located in São José in December 2013.

The first questions demonstrate the issue of the potential of organic FLV intake in Florianopolis and in the State of Santa Catarina, which proves to be a driving criterion in this sector. According to CE-SC, only 37% of marketed products comes from Santa Catarina. He further states that the market is growing "throughout Brazil because until today the trend is for people to increasingly consume organic products or products with a minimum of pesticides."

However, despite the growing market and the fact that the State producers do not meet the demands, CE-SC in his interview, refers to restrictive aspects such as the differentiation of the entire production chain (difficulties in distribution, and few sales points which would facilitate the purchase of products. "In CEASA there is no incentive policy, as a distribution channel." Other restrictive points have to do with low sales volume "... what we saw here is a wholesaler. So today, the low volume of sales of the organic product makes it go straight to the consumer market, and not here to wholesale, the CEASA."

The meeting was scheduled by email and confirmed by telephone, directly with the respondent (designated as EPA). Information on the interview content was also made available by phone. The interview took place in the EPAGRI headquarters, located in the city of Florianopolis in February 2014. A major incentive to organic FLV production is that, for EPA, "we are in a green belt in the region", besides the claim that "the markets say they want more." According to EPA, "there is a very interesting possibility of expansion of the organic product. All the conditions are reunited for organic production. There is an organization of producers around the market."

The restrictions presented are related to the difficulty of marketing on a large scale, "the CEASA is not the type of market for this production. In CEASA you find more profiteers than producers" and with the low increase in the number of producers, as well as in the consumption [despite the previous talk], "organic products have not been growing for a long time in Florianopolis. The sector has gone inactive. For 10 years it has had the same [producers]." The marketing suffers from the unattractive appearance of organic FLV and little advertisement of its qualities and benefits.

The contact was made by phone directly with an agent of NGO (designated as NGO). The interview took place inside the CEASA. Despite the short duration (about 40 minutes) some restrictive elements considered by the researchers appeared, such as devaluation by consumers. According to NGO, besides complaints about the price charged (considered as high) and the unattractive appearance of organic FLV "most [consumers] want to buy beautiful things and buy by the looks."

The NGO presents a solution to the issue of appearance suggesting an attractive packaging, "packaging and presentation of products is as beautiful as the imaginary, the presentation is less, and the packaging and awareness can solve this problem."

The contact was made by a third person known to the producer and to one of the researchers. The interview was conducted directly with the farmer (designated as PRT1) who trades within the CEASA.

Other producers were contacted by telephone and during that initial contact, no significant change was observed in the positioning of this segment, which eventually led the researchers to deem it sufficient.

However, the restrictions cited by PR1 were related to the lack of mastery of production technology for the benefit of the conventional technical knowledge: "I don't know, maybe I would not be able to produce because today we are used to having a little bit of pesticide, and so without it think it will be difficult." There is also the lack of incentive on the part of public agencies to produce organic FLV. PR1 presents as an example the financing of vehicles, machinery and equipment by the Federal Government, but could not answer whether these same machinery could be used in organic culture. The same restrictive elements cited by CEASA and EPAGRI were also arguments presented by the producer for non-production of organics.

The contact was made directly with the producer (designated as PRO). Unlike the 'conventional' producer, PRO has a more optimistic view regarding the production of organic FLV. However, restrictive issues were also presented during the interview. Below are some of the key sentences in the interviewee's speech, and the classification thereof:

"Consumers are increasingly demanding with regard to environmental protection, consumer awareness and the future of the planet." (booster)

"There are reports that the organic FLV improves people's health, saving with medicines and medical appointments, so the consumption of organics pays off". (booster)

"There is legal obligation to indicate that the product is organic, which increases our costs. Why not reverse, so that those who do not produce healthy foods should indicate that it is not organic and which pesticide was used?" (constraining)

"There is a lack of organic purchasing habits and/or the culture of buying organic is underdeveloped." (constraining)

"Most consumers still think the organic products are more expensive, and many still do not recognize that paying more may be worth it." (constraining)

The following are the main claims of consumers, especially the constraining conditions and the boosters for organic FLV consumption.

Constrains: Absence of quality pattern for products

C1: it's hard to find much quality. You can find something in a timely quality if you are lucky enough to arrive early. Sometimes there are good products there, but the quality varies widely.

C2: I stopped buying in ... [organic FLV sales point - LFLVo] because of this difference of pattern.

Boosters: Appearance of the shopping environment

C5: The appearance of [FLV point of sale - LFLV] is also what you eat with your eyes.

C3: It's better than the other sites.

C4: Location and appearance, for sure.

CC5: Quality and location of [LFLV] and of [LFLV], and the price at fairs.

CC4: Number one, price!

CC2: Funny I do not have that feeling with [LFLVo], perhaps because at the [LFLVo] when I want something special I go there ... I do not mind paying.

CC1: Yeah ... but there the price is higher, compared to other sites.

CC2: I think I struggle just to break with this thing that organic is luxury, with great urgency and necessity. Everyone knows, or everyone has children in school, right? The city can get into that. Why not making it an educational project?

The CEASA seems concerned primarily with economic/financial issues and admits that marketing of organic FLV is still small, and usually the manufacturer of organics does not make the distribution on site. However, the CEASA does not rule out the possibility. Reading between the lines, it seems to believe that the consumers' minds can change and facilitate the marketing of organic FLV in the future.

EPAGRI cares about the small organic farmers, and also agrees that organic FLV farming is already being sought. It appears that the profiteers make the process more expensive, and the association of small producers of organic FLV can be regarded as a way out of this problem.

The NGO notes that it is possible to deliver an improved appearance through packaging, avoiding an initial repulsion by the consumer, even if the products are unattractive, and thus preventing those who know little about the subject from not buying because of the initial image.

The conventional farmer believes that the lack of knowledge and government incentives stray the producers away from this type of cultivation. It is easier for them to do what they already know, which is to produce with pesticides.

The organic FLV farmer notes that the costs are greater for those who have to identify each organic product. It makes the process slower and more expensive. If the roles were reversed, the price difference could be smaller.

Consumers have an openness to products with higher quality, but certain aspects need to be corrected, such as the diffusion of advertisement of products by season to create a culture of consumption; improvement of convenience, that is, offering of easily accessible and widely distributed locations; image upgrade, i.e., care with the appearance of organic products, so that they can compete with the appearance of products developed with pesticides.

AGLE, B. R. et al. "Toward superior stakeholder theory". Business Ethics Quarterly, Charlottesville, v. 18, p. 153-190, 2008.

ANACLETO, C. A; PALADINI, E. P; CAMPOS, L. M. S. Avaliação da gestão da qualidade em produtoras rurais de alimentos orgânicos: alinhamento entre processo e consumidor. Revista Alcance, v. 21, n. 3, p. 500-517,2014.

CASWELL, J.A. "Labeling policy for GMOs: To Each his own?"AgBioForum, v. 3, n. 1, p. 305-309, 2000.

DONAIRE, D. Gestão ambiental na empresa. São Paulo: Atlas. 1999.

EMSHOFF, J. R. Managerial breakthroughs: action techniques for strategic change. New York: AMA-AMACON, 1980.

FERNANDES, D. M. M; KARNOPP, E. "A agricultura familiar e a cadeia produtiva de alimentos orgânicos: conquistas". RDE - Revista de Desenvolvimento Econômico, n. 29, p. 130-137, 2014.

FREEMAN, R. E. Strategic Management: a Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman. 1984. Disponible em <http://www.corporateethics.org/pdf/Strategic_Management_A_Stakeholder_Approach.pdf>. Acesso em: 23 nov. 2014

_____.; REED, D. L. "Stockholders and Stakeholders: a new perspective on corporate governance" California Management Review, v. 25, n. 3, p. 88-106, 1983.

_____.; HARRISON, J. S.; WICKS, A. C. Managing for Stakeholders: Survival, Reputation, and Success. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007

GOLDSCHMIDT, A. "Engajamento com stakeholders e o relatório de sustentabilidade". In: ROCHA, T.; GOLDSCHMIDT, A. Gestão dos Stakeholders: como gerenciar o relacionamento e a comunicação entre a empresa e seus públicos de interesse. 2010. São Paulo: Saraiva

IFOAM – ORGANICS INTERNATIONAL ACTION GROUP. The full diversity of Organic Agriculture: What we call Organic. Disponible em: <http://infohub.ifoam.org/sites/default/files/page/files/full-diversity-organic-agriculture-enweb_0.pdf>. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2013.

KAUFMANN, P.; STAGL, S.; FRANKS, D.W. "Simulating the diffusion of organic farming practices in two New EU Member States". Ecological Economics, v. 68, n. 10, p. 2580-2593, 2009.

KIND, L. "Notas para o trabalho com a técnica de grupos focais". Psicologia em Revista. v. 10, n. 15, p. 124-136, jun., 2004

KNOREK, R. "Agronegócio: um projeto como forma de alavancagem para o desenvolvimento da economia local-regional voltado para a agricultura familiar da 26ª SDR". Cadernos de Economia (Unochapecó. Online), v. 28, p. 49-58, 2011.

LIMA, P. F. C. Alimentos orgânicos: produção e perfil do consumidor na cidade de Manaus. Dissertação. 2014. Universidade Federal do Pará. Mestrado Profissional e Processos Construtivos e Saneamento Urbano. 2014.

LYRA, M. G; GOMES, R. C; JACOVINE, L. A. G. "O Papel dos Stakeholders na Sustentabilidade da Empresa: Contribuições para Construção de um Modelo de Análise". RAC, v. 13, p. 39-52, 2009.

MELLO, M. A. de; SCHMIDT, W. "A cadeia produtiva do leite e a agricultura familiar do Oeste de Santa Catarina: possibilidades para o desenvolvimento". Cadernos de Economia. v. 6, n. 10, p. 7-30, 2002.

PAVÃO, Y. M. P; DALFOVO, M. S.; ESCOBAR, M. A. R.; ROSSETTO, C. R. "A influência dos stakeholders no ambiente estratégico de uma cooperativa de crédito: efeitos da munificência". Revista Ciências da Administração. v. 14, n 34, p. 24-38, 2012.

RIBEIRO, H. C. M; COSTA, B. K; FERREIRA, M. A. S. P. V; SERRA, B. P. de C. "Produção científica sobre os temas Governança Corporativa e Stakeholders em periódicos internacionais". Contabilidade, Gestão e Governança. v. 17, n.1, p. 95 – 114, 2014.

SAVAGE, G. T.; NIX, T. W.; WHITEHEAD, C. J.; BLAIR, J. D. "Strategies for assessing and managing organizational stakeholders". Academy of Management Executive, v 5, n. 2, p. 61-75. 1991.

SAVITZ, A. W. A empresa sustentável. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2007.

SHROPSHIRE, C.; HILLMAN, A. J. "A longitudinal study of significant change in stakeholder management". Business & Society, London, v. 46, n. 1, p. 63-87, 2007.

SILVA, A. L.; LOURENZANI, A. E. B. S. "Modelo sistêmico de ocorrência de ações coletivas: um estudo multicaso na comercialização de frutas, legumes e verduras" Gestão & Produção (UFSCAR. Impresso), v. 18, p. 159-174, 2011.

TACHIZAWA, T. Gestão ambiental e responsabilidade social corporativa: estratégias de negócios focadas na realidade brasileira. São Paulo: Atlas, 2002.

TORJUSEN, H.; LIEBLEIN, G.; VITTERSO, G. "Learning, communicating and eating in local foodsystems: The case of organic box schemes in Denmark and Norway". Local Environment, v. 13, n. 3, p. 219-234, 2008.

VEIRIA, S. F. A; COSTA, B. K; OGUIDO, W. S; CINTRA, R. F. "Pesquisa no turismo utilizando a teoria dos stakeholders: revisando a literatura". Revista Ciências Administração. v. 17, n. 3, p. 796-818, 2011.

----

We highlight that this research was only made possible through the financial support of the Foundation for Research and Innovation of the State of Santa Catarina - FAPESC.

Hence, our sincere thanks to FAPESC!

1. Doutor em Administração e Turismo e Professor do IFSC – Instituto Federal de Santa Catarina e-mail: deosir@ifsc.edu.br

2. Doutorando em Administração e Professor da UFSC – Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina e-mail: marcelodeluca2@gmail.com

3. Doutor em Administração e Turismo e Professor do PPGA/MPA da Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná – UNIOESTE e-mail: adm.miura@gmail.com

4. Doutor em Administração e Turismo e Professor do PPGDTSA da Universidade Federal de Pelotas – UFPel e-mail: elvis.professor@gmail.com

5. Doutor em Engenharia da Produção, Professor e Vice-Reitor Acadêmico da Universidade Alto Vale do Rio do Peixe – UNIARP e-mail: andersonmartins@uniarp.edu.br

6. Doutora em Ciências e Professora da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina – UFSC e-mail: resfloripa@yahoo.com.br